It has been over twenty years since my dear friend DONDI WHITE died. He joined the ancestors on Friday, Oct 2, 1998. I am going to take this opportunity to share some very personal memories and history about him and our friendship and of course I will share many photos of DONDI and his extraordinary work.

In the spring of 1980 a remarkable thing occurred. The father of my friend, Merryl Esses, took a sudden and keen interest in graffiti and decided to create what I can only accurately refer to as “a graffiti preservation project”. This revolutionary two month project is known alternatively as “ESSES STUDIO” or “THE GRAFFITI 1980 STUDIO” and you can read a detailed history about it elsewhere on this website.

The studio was the inspiration of Merryl’s father, the late Samuel Esses. The project was run exclusively by FUTURA and me. We did our best to facilitate the creation of a grand array of graffiti canvases in a small window of time (two months). We did so by inviting many great subway artists of the time to come and throw down at the studio. We were fortunate that we had good friendships at the time with style masters and legends alike. From the SOUL ARTISTS meetings that the late Marc “ALI” Edmonds organized, we had already developed great relationships with guys like TRACY 168, NOC 167 and STAN 153 and they came early and painted at the studio and immediately set a very high standard for the canvases.

Simultaneously, a graffiti crew known as ROC STARS (“Rock On City”)—some of whom (such as CRASH) we knew personally— were eager to make canvases at the studio. They were among the most prolific style masters of the time, hitting the #1 Broadway Local Line every week with new window-down burners. The ROC STAR roster was KEL 139, SHY 147, CRASH, COS 207 and Kel’s younger brother, MARE 139.

As so many different writers with so much talent continued to show up and paint great canvases during the span of the studio experience, FUTURA and I couldn’t believe the good fortune of what was happening right before our eyes. When word got out and so many of the great subway painters of the period—artists like SEEN and T-KID 170— began arriving to paint canvases at ESSES STUDIO, FUTURA and I were amazed as the roster of talent began exceeding our wildest expectations.

I remember clearly when KEL told us that he was trying to get DONDI to come and do a canvas at the studio. KEL had been a close collaborator with DONDI on many subway paint jobs, particularly on the BMT lines where DONDI cut his graffiti teeth. KEL knew DONDI very well, as did his crew-mate CRASH. My good friend and graffiti collaborator NOC 167 also had a long-standing friendship with DONDI.

DONDI hailed from the East New York section of Brooklyn, all the way at the end of the #2 Line. He did not go to the 149th Street Grand Concourse train station in the Bronx where many writers congregated and he clearly put a premium on his privacy and low profile.

DONDI was an elusive figure at the time. DONDI hailed from the East New York section of Brooklyn, all the way at the end of the #2 Line. He did not go to the 149th Street Grand Concourse train station in the Bronx where many writers congregated (“The Writer’s Corner” or “The Writer’s Bench”) and he clearly put a premium on his privacy and low profile. But his subways spoke for themselves. For years I had seen his work on the BMT’s (my high school was on the LL line). I saw his backward straight-letter DONDI and NACO pieces go by almost every day, and through Henry Chalfant’s photos, I was coming to appreciate that he was a style master of the highest caliber as well. With his straight-letter whole car on the #2 Line, “Children Of The Grave, Part 2”, DONDI set the graff world on fire and justly cemented his place atop the NYC subway painting hierarchy of the time.

In March of 1980 there were many train painters who were held in enormous regard and of course no one’s “favorite graffiti artist” list is ever going to be universally agreed upon. From my vantage point, at the time, the two truly great giants of NYC subway painting were LEE and DONDI, with BLADE and SEEN trailing close behind with honorable mention. The idea that DONDI might come and paint at the studio seemed too amazing to even consider, and FUTURA and I remained skeptical at best.

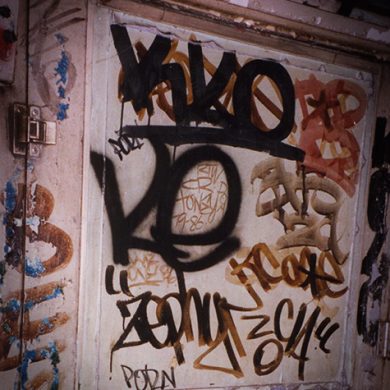

We were a month into the studio experience. One afternoon, FUTURA and I stepped out for a brief minute to grab something from the local hardware store. As we returned to the studio, we stood in disbelief, staring at a “DONDI” tag outside the studio, executed with a fat black magic marker. Funny (not funny) was that we had done our best (and we had experienced a surprisingly good track record up until that point) to maintain, with our only tool—constant desperate pleading—a “no tags” policy on exterior of the building that housed the studio. The studio was located on 75th Street between First Avenue and York Avenue in Manhattan—a high-rent part of town. We knew that we had to play it cool and that blitzing the outside of the building with tags would probably get us kicked out. To be fair, DONDI didn’t know the rules, but looking back, I doubt he would have made a point of following them anyway. DONDI was always his own man. He always charted his own path. He was not one to seek advice and rarely followed the lead of others. On that day he simply wanted to announce his arrival and so he did.

To be fair, DONDI didn’t know the rules, but looking back, I doubt he would have made a point of following them anyway. DONDI was always his own man. He always charted his own path.

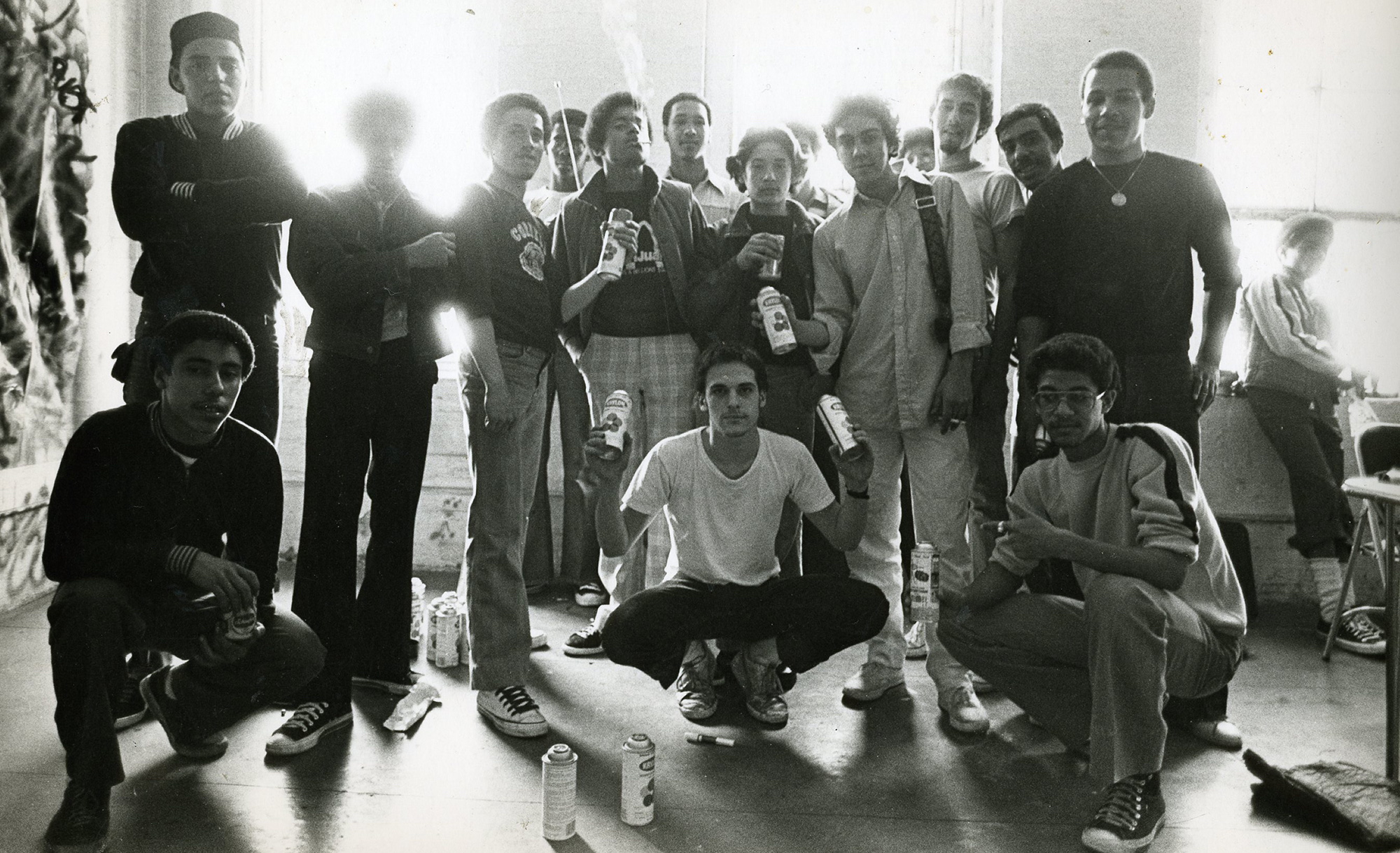

DONDI came to the studio that day accompanied by a significant entourage. DONDI came up as a graffiti writer as a member of a Brooklyn graff crew called “The Odd Partners” (T.O.P.). By March 1980 DONDI had created his own graff crew which he called “Crazy Insides Artists” (C.I.A.). His entourage that day was a who’s who of the CIA Crew. He was accompanied by PETE, EDDIE, LOVIN 2 (aka AERON), DURO (previously SONO), MOUSEY 56, KID 56 (brother of legendary graffiti writer FDT 56), FACT (aka DR. PEPPER), RASTA CIA (who shortly thereafter changed his name to RASTAR to avoid conflict and confusion with the original RASTA, RASTA RTW).

As luck would have it, a photographer named Rafael Pasquera was present on that day and he snapped an extraordinary group shot which I am sharing with you below. Appearing in this photo are all the members of Dondi’s entourage from that day and the other artists who were fortunate enough to be at the studio that day.

Coinciding with the studio experience was a project I referred to earlier. A precocious mastermind named Marc Edmonds (“ALI”) was the president of an unconventional graffiti crew he called THE SOUL ARTISTS (S.A.). He created this Manhattan-based writing crew in the early 1970’s just as the NYC graffiti movement was beginning to flourish. By 1980 he had reinvented the Soul Artists as a loose affiliation of his present and former graffiti cohorts positioned for pursuing legitimate art endeavors. With an actual workshop at our disposal (106th Street and Columbus Avenue in Manhattan) we held weekly Monday night meetings that were regularly attended by graffiti writers, journalists, activists and the otherwise curious. This story is important because within a week DONDI joined the SOUL ARTISTS fray.

DONDI was a true Brooklyn denizen. In 1980 Manhattan was not part of his geographic wheelhouse but he immediately began hanging out with us up in Manhattan Valley. The addition of DONDI to our SOUL ARTISTS lineup was nothing short of a “pinch me I’m dreaming” miracle to us. FUTURA, ALI and I were equally amazed and humbled that DONDI, the mysterious graffiti king from Brooklyn, actually took a liking to us and wanted to be a part of our ragtag group.

It was a strange time for THE SOUL ARTISTS. Tensions had emerged over the ESSES STUDIO project. ALI was away for an extended period in California on a solo art project (painting a mural in a recording studio) when the GRAFFITI 1980 studio project occurred. Upon his return to New York ALI was upset that the graffiti studio was not being considered an official “Soul Artists Project”. This put a strain on the group just as DONDI segued into the mix. I don’t think it was a particularly noticeable issue for him despite the fact that we were starting to splinter off. Some of us were getting important solo gigs, like Futura’s soon-to-be-forged historic relationship with the rock band THE CLASH, while ALI began his own musical career. Trying to remain as a collective just wasn’t a feasible option anymore.

During this period, as journalists like Richard Goldstein (from The Village Voice) and Steve Hager (from The Soho News) took a big interest in us, supporters emerged from all kinds of places. “New Wave” dance clubs had popped up all over Manhattan. Something about our personalities and/or outside-the-law status as subway painters appealed to some of the owners and managers of these nightclubs, a number of whom had their own interesting “family connections” and backstories. Many of these clubs and their respective owners became gatekeepers and powerbrokers for what was considered “hip” and “cool” in the spring and summer of 1980. As the SOUL ARTISTS we frequented these clubs and developed rapports with some of the managers and owners and even ended up doing commissioned graffiti paint jobs in a number of dance clubs around town. This created a nice situation for us, giving us entre into a scene where we began to make viable art/business connections.

This piece of the story is important. Patti Astor has recounted that a chance encounter outside a famed NYC club called the Peppermint Lounge led to her future as the creator of the FUN GALLERY—the first gallery to give solo exhibits to graffiti writers. As Patti recalls the incident, we were having trouble getting past the doorman and his velvet rope until she intervened on our behalf and falsely claimed we were with her. With her magnanimous gesture toward a group of very young strangers she ended up meeting DONDI, FUTURA and myself that night. All three of us went on to exhibit at her future gallery, “the Fun”.

DONDI and I forged an immediate strong bond upon meeting each other in March of 1980. We came from diametrically different backgrounds but we bonded, as corny as it sounds, like two long-lost brothers. Within a week, upon meeting, I was a guest at his family’s house, meeting his mother as she offered me a grilled cheese sandwich for lunch, and amazing me with her offhanded mention that she had not set foot in Manhattan in over a decade.

Graffiti was always the glue and the connecting point for so many of us from the controversial culture of graffiti. Meeting other graffiti writers, historically, dissolved and devolved many of the unnecessary social and societal barriers that were, sadly, part of many other people’s day-to-day lives. We saw our fellow graffiti writers—particularly those whose graffiti we had real admiration for—first and foremost as fellow artists from what was then a very secret society. As graffiti practitioners seeking out other graffiti practitioners we remained free of much of the stigma that plagued civil society outside our graffiti community. Any and all so-called “differences”—class, race, et al—were, thankfully, 100% irrelevant to us. That is why graffiti, in NYC in 1980, was a cultural bouillabaisse, and rightly so. No doubt DONDI had a particularly distinctive firsthand perspective on many of these complex issues. DONDI was born in 1961 to mixed race parents. I discussed this with him when I did a “for no particular reason” video interview with him in January 1995 and I will share some of his responses at a later date.

We saw our fellow graffiti writers—particularly those whose graffiti we had real admiration for—first and foremost as fellow artists from what was then a very secret society.

After his death in 1998 I was asked to write comments about DONDI for many websites and publications. I always agreed, feeling that spreading the word about DONDI was imperative. This process of honoring DONDI culminated in the publication of my biography of his life and work titled “DONDI WHITE; STYLE MASTER GENERAL” (published in 2000). The book was well received but was printed in limited numbers and has remained out of print for decades.

With that in mind I’m using this opportunity to revisit the legacy of DONDI WHITE. I hope you enjoy it and are inspired by his life and work.

I wrote this piece (below) for a magazine four months after Dondi’s death.

My sentiments remain the same.

Time does not heal.

Time just smoothes down the sharp edges…

“DONDI WHITE was a visionary and my best friend. Like all his friends around the world I struggle to accept that he is gone. As a person DONDI was many things to many people. In his passing many close to him realize that each of us knew a different DONDI. He was a renaissance man in every sense of the term. He had an endless range of knowledge and interests and was always passionate and committed to his work. He was a man of strong conviction. He was self-disciplined to the extreme and maintained a near-monastic order over his own life. He was capable of great warmth and generosity but chilling coolness as well. He was steadfast in his choices and was not one to waver. DONDI and I made a lot of art together. He introduced me to the #2 Yard and I showed him the #3 Yard. He helped me improve my piecing and I gave him some illustration tips. He told me he wanted to succeed “on all fronts”. We started transitioning to canvas at the same time and we became associated with two downtown galleries early on—51X and the Fun Gallery. We both worked on the production of the film “Wild Style”. In 1982, with FUTURA, we left NYC to represent our work at a university gallery in California. Many other long distance art trips would follow. FUTURA went on to be represented by a Paris gallery. DONDI and I were represented by a gallery in Amsterdam. Throughout the first half of the 1980’s Dondi’s career as an artist took him to Europe and Asia countless times. During the same period DONDI and I did our favorite collaborations on the subway as well. We made little distinction between graffiti and our “fine art”—the approach to each were blurred and juxtaposed. Rumblings that the interest in “legitimate art careers” led to an overall decline in NYC subway painting activity is, in our case, inaccurate. The “aboveground movement” and the “below ground world” nourished each other. DONDI was years—actually decades—ahead of his time. Aspects of his work and stylistic subtleties of his invention have set graffiti standards forever. Train pieces he did in 1979, “ROLL” or “MR. WHITE”, look as fresh and vibrant today as they did the day he dreamed them up and executed them to steel. In terms on inventiveness, originality and technical virtuosity DONDI remains in a league of his own.

Since DONDI left us in October I have read so may heartfelt letters and messages of condolence from people all over the world. It seems like some folks who didn’t have the pleasure of knowing DONDI are taking the loss as deeply as those who knew him. Perhaps graffiti artists know that he crafted a blueprint that we all rely on and we’re forever grateful. Perhaps we’re acknowledging the things that bind us, even when they are so intangible. Dondi’s work above and below ground are part of a mandatory lesson. As we learn more about DONDI and his amazing art, we learn more about ourselves.”

—Zephyr (February 1999)

Dondi, age 10

Early Dondi drawing, 1972 (age 11)

Dondi captures Julius “Dr. J” Erving, 1974

Dondi with his brother Al (1976)

Dondi and friends on the roof of his building; Van Siclen Ave., Brooklyn (1978)

Dondi in his bedroom, circa 1980, with Greg 167, Slave, Mr. Jay and Lovin 2. Photo: Martha Cooper

Dondi in his basement with Lo, Lec and Deal, 1979. Photo: Martha Cooper

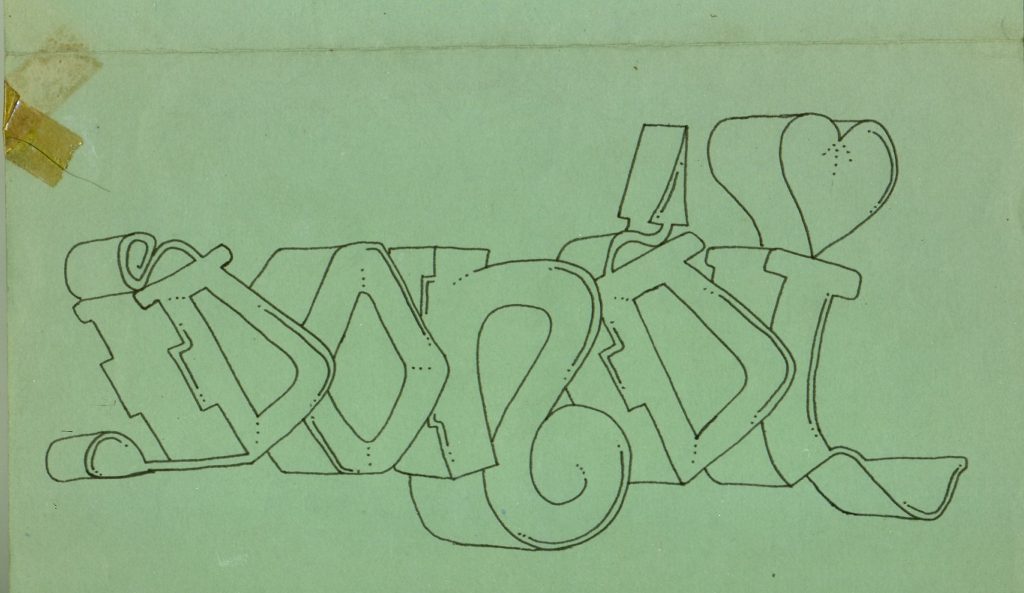

Early Dondi outline from 1977

Early Dondi subway piece, circa 1978

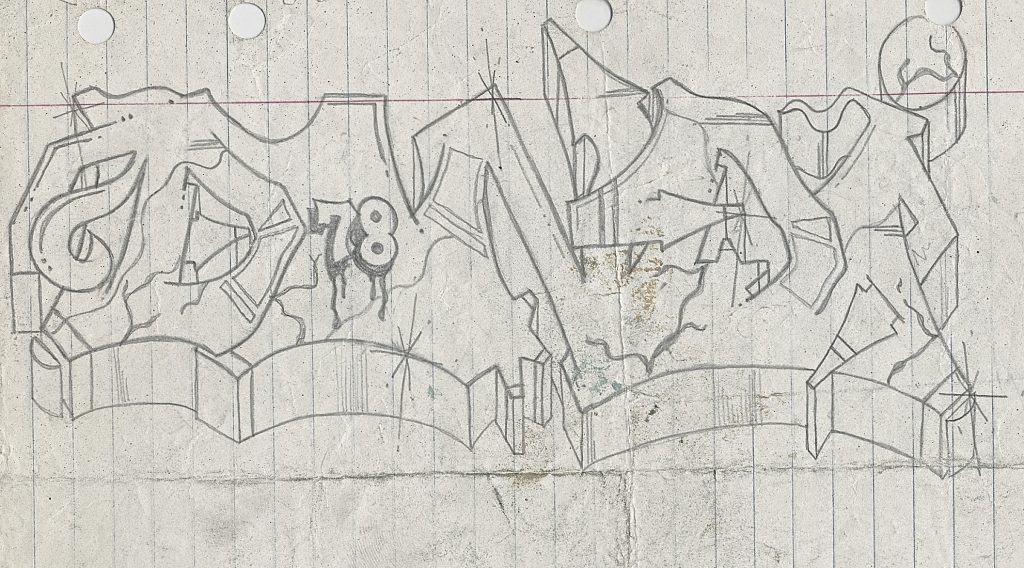

Early Dondi outline “Dondi Mom ’78”

Earliest photographed Dondi train piece, circa 1977

One of Dondi’s early trademarks was doing backward pieces. Here’s an early “Dondish” backward straight-letter.

Another great backward piece. “Naco”. For full effect Dondi even did a backward “Naco” tag in the “N”.

Dondi piece on JJ train, circa 1978.

“NACO CIA”, 1978

A quick NACO piece, 1978

“2 MOM”….Inscribed “From DONDI, 1978” in the heart

Another very early DONDI piece from 1977

The legendary “UNCLE DONDI” car on the BMT’s, circa 1978

NACO wholecar on the BMT’s. 1978

Another great NACO blockbuster on the BMT’s

NACO throw-up on a clean #2 IRT car

A colorful “DONDISM” piece from 1978

Blurry shot of a classic early backward DONDI straight-letter on the #2 line

Dondi and Fuzz with the Schaefers, 1978

The character sketch Dondi used for his “Dondish” backward car, 1978

A cool character by Dondi on a “CASH 2” piece, 1978

CASH 2 piece by DONDI

CASH outline

“MARE” piece by Dondi from the “Cash-Mare-Kel” car

Platform close-up of a tasty NACO window down

The early Dondi masterpiece, “Children Of The Grave, part 1” wholecar

Sketch for “Children Of The Grave, part 1” wholecar

Dondi’s half of the “Dondi 1, Kid 56” straight letter on the BMT’s

Kid 56 and Dondi in the New Lots train yard posing in front of their “Dondi-Kid” backward masterpiece

Dondi’s character sketch for the “Dondi-Kid” car

A great “BEV” piece by Dondi, 1978

A sweet “Naco” burner

Outline for the “Naco” piece

Dondi with the sweet “Bev 79” outline (for Beverly)

This piece was actually done on Dondi’s roof on Van Siclen Ave.

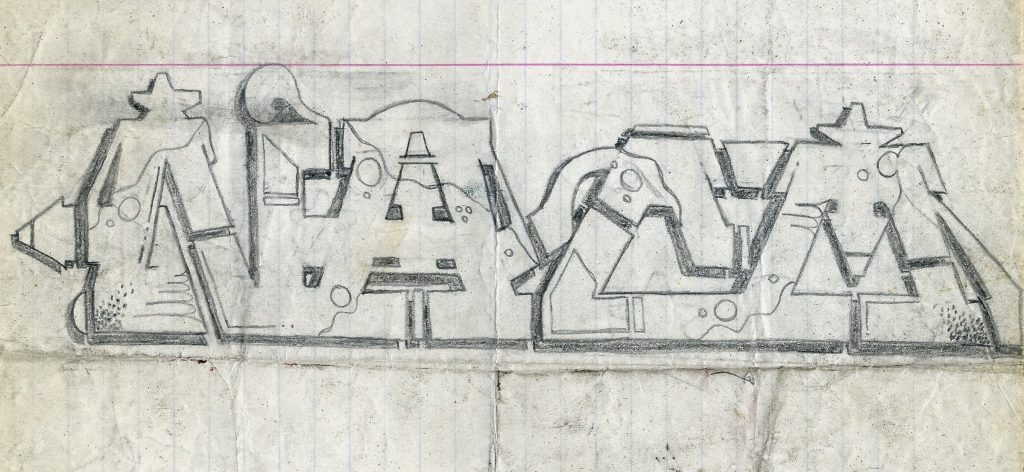

Early NACO outline

Early NACO outline

Early NACO outline

Early NACO outline

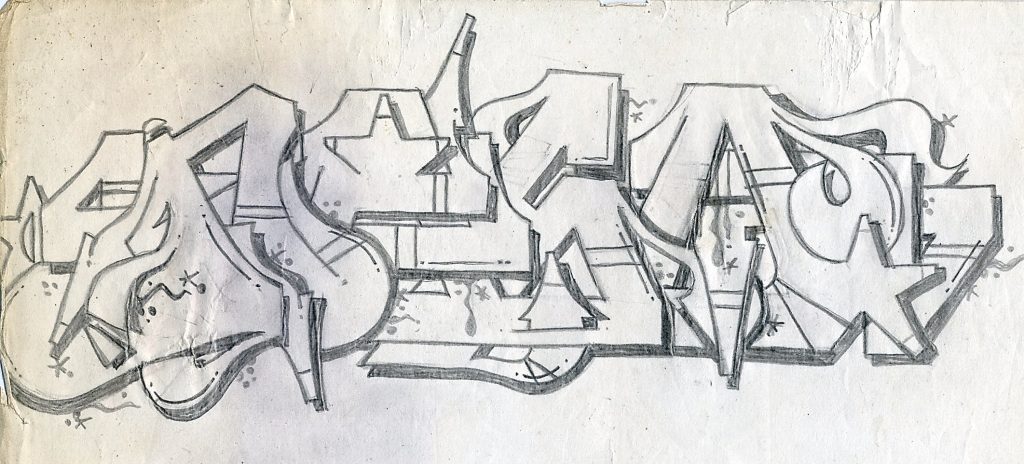

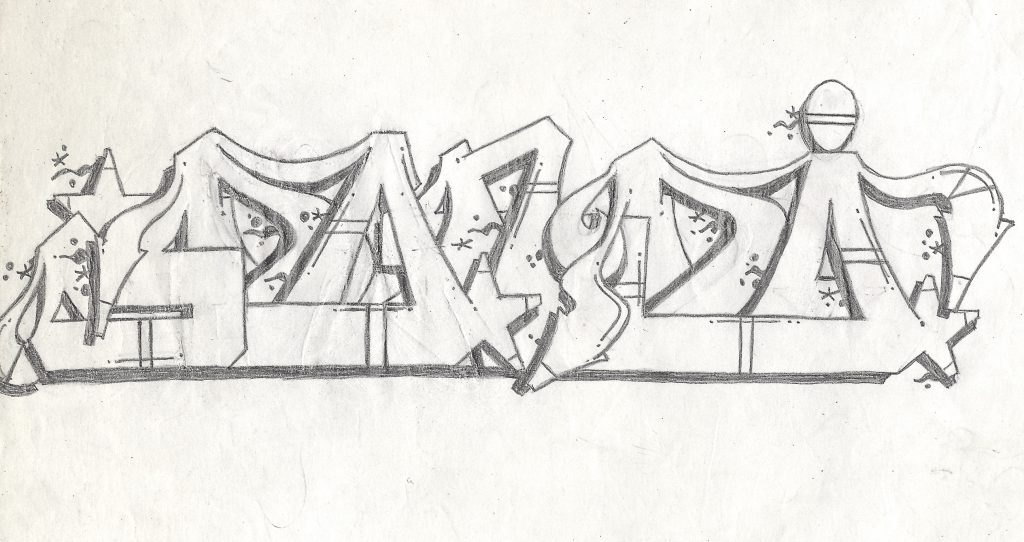

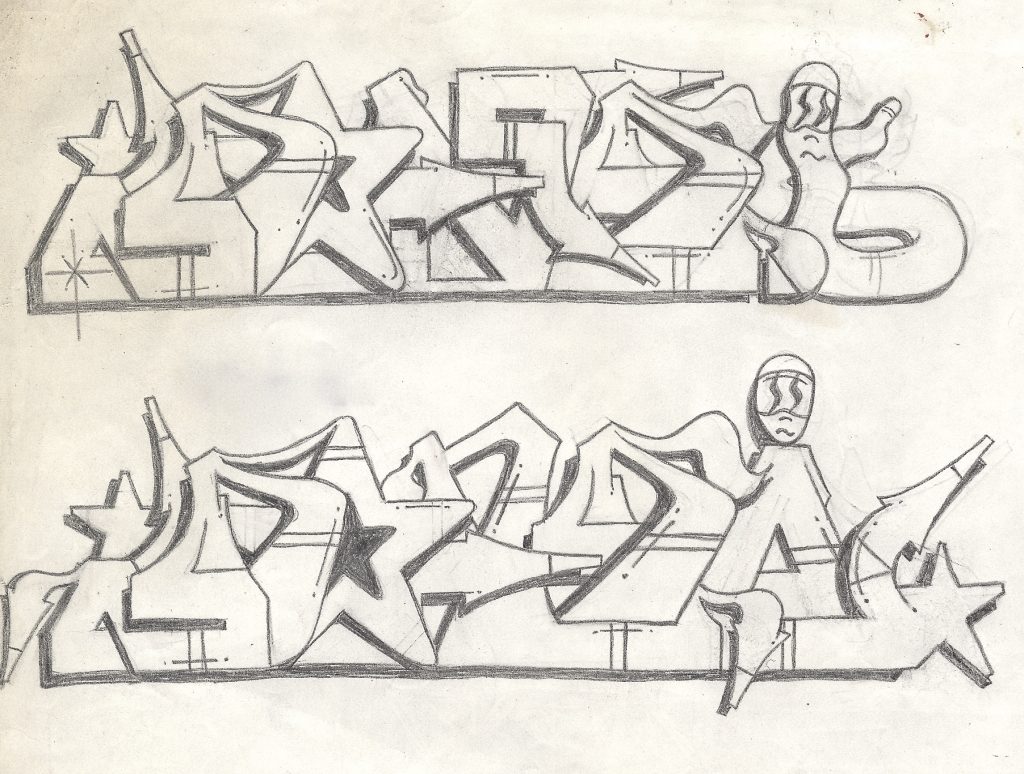

Early DONDI outline

Early DONDI outline

Early DONDI outline

Early DONDI outline

NOC outline by DONDI

2 HOT outline by DONDI

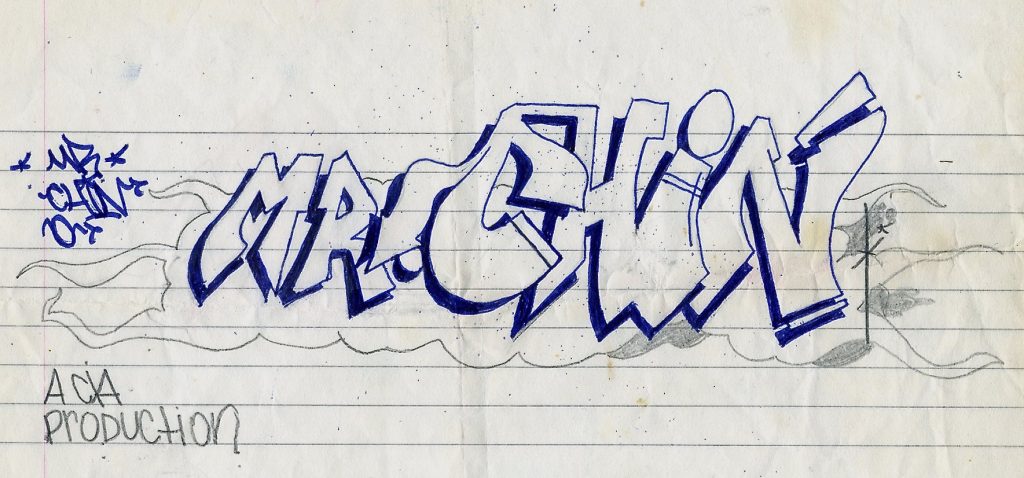

MR. CHIN outline by DONDI

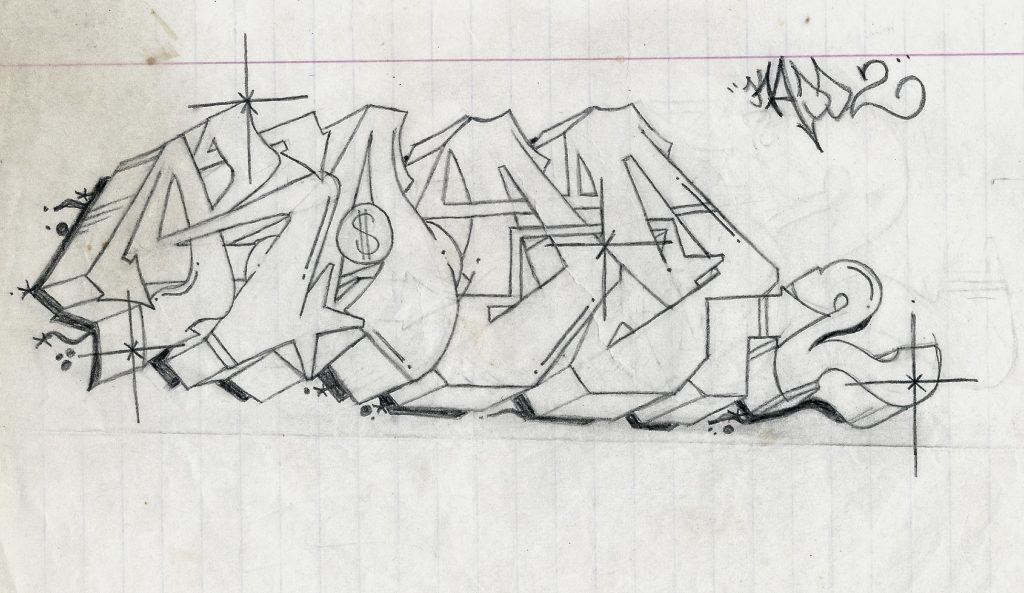

KADD 2 outline by DONDI

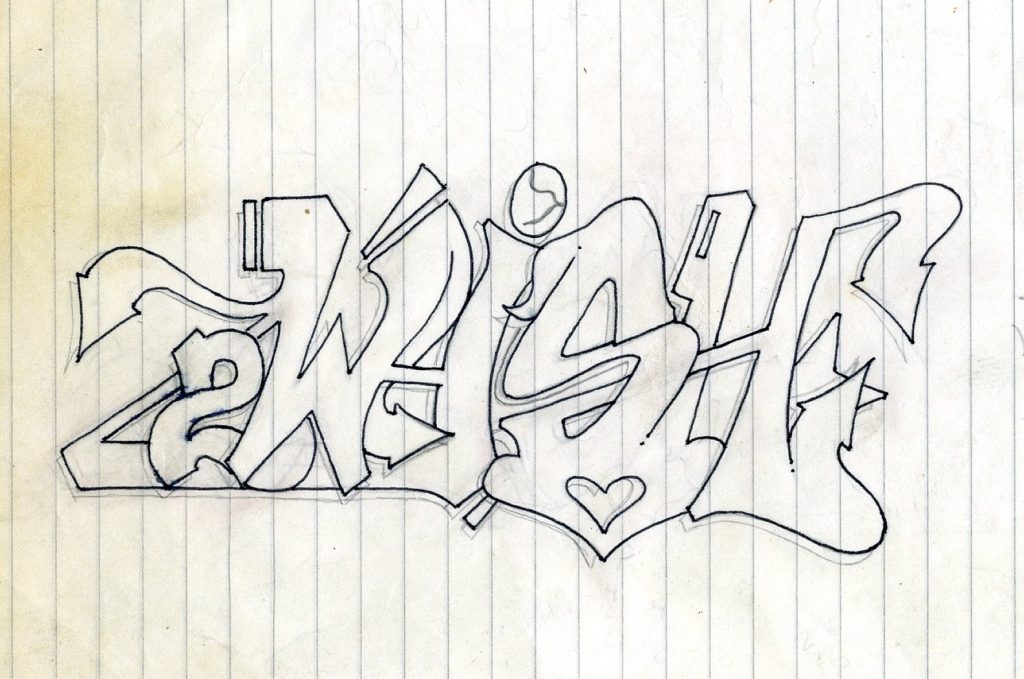

2 WISH outline by DONDI

WORK outline by DONDI

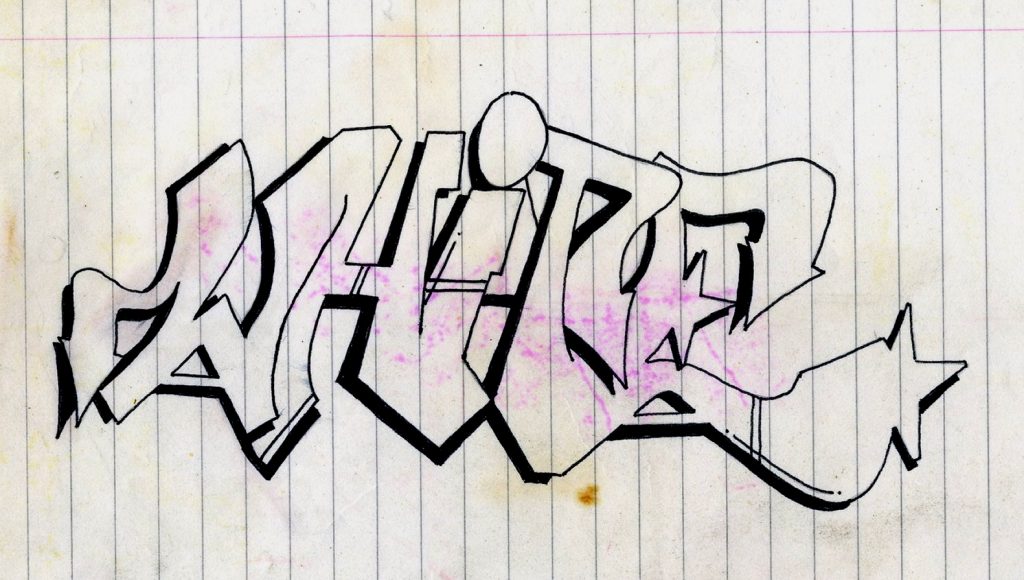

WHITE outline by DONDI